Finding a Place: The New Negro Movement and Modern Art

What happens to the idea of regionalism when an entire culture is new? In a post-colonial society, recently parted from England, eighteenth century Americans were free to create their own identity. In the nineteenth century, African Americans faced the same opportunity to discover their identity during the Reconstruction, in a post-slavery society. Black artists continued to paint and sculpt their experiences, and the height of Black art in America occurred during the New Negro Movement, or better known as the Harlem Renaissance.

Black American artists worked during the same time as White American modern artists, yet the latter is studied more extensively throughout art history and taught in a majority of art history curriculums, while little remains known or taught on Black American Artists. Most people have heard the name Georgia O’Keefe, but few would know the name Meta Warrick Fuller. This discrepancy has remained a challenge for the art historical community, conflicted on whether the works of the Black modern artists should be compared to and considered alongside their White contemporaries, or set apart as their own artistic movement.

This essay will discuss the intellectual origins of the New Negro Movement, and three key artists who helped form the ideas of regionalism and identity for Black Americans during the Harlem Renaissance. Much is to be shared on this subject, and there are many Black artists who contributed greatly to creating an American identity, but due to the brevity of this essay, the focus will remain on the intellectual origins and the pioneers of Black American art, which include writer Alain Locke and artists Meta Warrick Fuller, Edmonia Lewis, and Aaron Douglas. If this essay were to be an anthology, the subsequent essays would include the significant contributions of Henry O. Tanner, James Van Der Zee, William H. Johnson, Palmer Hayden, Romare Bearden, and Jacob Lawrence, among other prolific Black artists of the last few centuries.

As you read, you’ll notice parenthetical citations. Those are there if you’d like to explore further, and a list of these works cited is listed at the end.

Modern Art and the New Negro Movement

While a large swath of American artists sought out their identity apart from Europe, another group of American artists were exploring their relationship with Africa. As Europe endured war-torn years, Africa bled as well, with a generation of families removed from its coasts and dispersed onto another. The African American in the early twentieth century was not long separated from slavery and was no stranger to segregation. The history told by their parents and grandparents were still fresh in their ears, and the stories of their past with their hopes for the future memorialized in African spiritual songs. This African American—a new American—experienced freedoms that their elders had hoped for, and the term “free” took on a new meaning. The enslaved African American’s identity had first stemmed from their native lands, then had to assimilate to life in slavery in America, and only a percentage were able to experience life as free people in this same land. The term “African-American” is much newer than the term “American.” The New Negro Movement, later referred to as the Harlem Renaissance, was a time of intentional development of the arts and cultural identity of Black Americans which began in New York in the early twentieth century.

The American artist’s primary focus was separation from Europe, recognizing the need for an internal source of guidance. American critic Paul Rosenfield stated that“we had been sponging on Europe for direction instead of developing our own (Corn, 9).” America’s lack of 7,000 years of cultural baggage to carry into the present day and into the future as it searches for its identity is something to be admired from the viewpoint of modernism. If modernism is to be concerned with the isolation of “distinctive appearances of the age,” then America was in a unique position since there was no ability to look back—there was only the present and an undetermined future (Harrison, p. 189).

In the early twentieth century, American painting, furniture, décor, and ceramics could be created without carrying the weight of ornament steeped in tradition. This created room for experimentation and a freedom of creativity emerges because there is no conscious holding the maker back by oath to historical methods of making. With a clear, creative mind, the cultural development of the nation is not impeded, but instead propelled forward. American artists like Georgia O’Keefe, Alfred Stieglitz, and Charles Demuth cut ties with European tradition of artmaking and focused their subjects on the landscape, the people, and the industrialization which characterized their America. These modern artists clung to the intellectual claims like that of French wartime pacifist, Romain Rolland, who implored American artists to “Be free! Do not become slaves to foreign models…You are fortunate. Your life is young and abundant. Your land is vast and free for the discovery of your works. You are at the beginning of your journey, at the dawn of your day. There is in you no weariness of the Yesterdays; no cluttering of the Pasts (Corn, p. 11).” With this and other essays from European theorists like Adolf Loos exclaiming that “those who measure everything by the past impede the cultural development of nations and humanity itself,” American modern artists felt as if Europe was beseeching that they detach themselves culturally and form their own identity (Loos, p. 32).

Alain Locke, America’s First Black Rhodes Scholar

Alain Locke, c. 1946

America’s First Black Rhodes Scholar

Produced around the same time of the writings from Rosenfield on cultural and regional identity were the writings of America’s first Black Rhodes Scholar, Alain Locke. Alongside the creation of visual art works by Georgia O’Keefe, Alfred Stieglitz, and Charles Demuth were the works of Black American artists like Palmer Hayden, Aaron Douglas, and James Van Der Zee. Each writer and artist sought to determine the definition of Americanness, defining what makes the vast space of America a place which they can call their own. Yi-Fu Tuan, a Chinese-American geographer, mentions in his essay Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience that “what begins as undifferentiated space becomes place as we get to know it better and endow it with value (Tuan, p. 6).”

The idea that Black artists could work in such a way that defined their cultural identity made them regionalists in their own rights, making the space of America their own place. These Black American artists were modernists by Baudelaire’s definition since they were also concerned with the aforementioned “distinctive appearances of the age.”

For all the American modern artists, none could move the needle on forming a culture and developing an art form that is truly American without the acknowledging the presence of their respective pasts. The difference is that Black American modern artists were encouraged to look to Africa and their migratory journey for inspiration, while White American modern artists sought to sever the influence of Europe on their artistic identity. Alain Locke cautioned Black artists against the modernist trends of New York and Paris, and instead encouraged that African art would be “an important source of aesthetics and iconography that would be meaningful to their race (Driskell, p. 106).” Locke recognized that in working this way, Black artists could fulfill the needs of thousands in the Black community.

A Desire for Security

What needs were Locke referring to that needed to be addressed among Black constituents? In the essay The International Aspects of Regionalism, H.W. Jansen speaks of Grant Wood, a White American painter working during the Great Depression. The Great Depression and the events leading up to it caused an identity crisis, leaving many Americans wondering if the space they inhabited was safe enough to call home and “endow it with value.” People were searching for realities to hold on to, and Wood’s staunch figures in American Gothic, appearing unscathed by the devastation of the depression, provided such a reality. Wood’s idyllic depictions of rural life in America provided a sense of stability and security untouched by the depression (Jansen, p. 6). This substitute reality is what the public needed during a time of great economic and political devastation. What the Black community needed was similar, a sense of stability and security in their new space, and place that affirmed both their individual and racial identities (Driskell, p. 107). Marsden Hartley’s On the Subject of Nativeness discusses regionalism as a desire for security of place amid the disorder and stress of the Great Depression, and this remains true for the Black American modern artist, whose work helped create an appreciation of place that helps to deal with social and cultural upheavals of their time (Cassidy, p. 228).

Black American Art and Regionalism

All American modern artists sought to form a cultural identity which represented their American experience. Yet, there is the tension of post-colonial scars—that of slavery, war, and dissension—within American history that greatly impacts our cultural identity. Wendell Berry wrote in The Regional Motive about incorporating our past into our modern artistic aspirations: “Shall we heal those scars…or shall we enshrine the scars and preserve them as monuments to the so-called glories of our history (Canizaro, 38)?” The question here rises if the Black artists inspired by Locke were enshrining the scars of America’s past by incorporating African symbolism and iconography into their work. Could American art ever be truly “American” if it failed to incorporate both the triumphs and the pitfalls this country has endured in its short history? Rosenfield, not in particular speaking about the Black artist but unintentionally including them in this statement, believed “that the kind of artist…someone who stayed at home, bled himself organically into the very fibers of American existence, and sang this country’s joys and tragedies in transcendent language—could be found (Corn, p. 13).”

Meta Warrick Fuller

Meta Warrick Fuller is among the first to be attributed with the idea of exploring African iconography as a Black American artist. Fuller was born in 1877 to a Black middle-class family in Philadelphia. She attended the Pennsylvania Museum and School for Industrial Arts from 1894 to 1899 (now known as the Philadelphia College of Art) and continued her studies at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia from 1903 to 1907. Prior to attending the Academy of Fine Arts, Fuller had already established herself as an artist in Paris, having been a student of Auguste Rodin and exhibited at the l’Art Nouveau. Very little of Rodin’s influence is seen in her work, however, since Fuller did not work in an impressionistic manner like many of her contemporaries. The faces and busts of her figures have uniquely African characteristics, with full lips and distinct cheek bones. For her subject matter, she turned to African songs and folktales as inspiration, being one of the first Black American artists to create work that was not just a replication of European technique or themes.

Meta Warwick Fuller

American poet, painter, theater designer, and sculptor

In the search for African American identity as it relates to regionalism, we begin with Meta Warrick Fuller because her work coincides with the writings on cultural identity by Alain Locke. Both were working before the New Negro Movement, or Harlem Renaissance, was underway, and both of their contributions created a pathway for Black artists to step onto as they sought the idea of place and identity. Fuller’s 1914 bronze sculpture, Ethiopia Awakening symbolized the emergence of the New Negro, and whose figure resembles a mummy with legs bound tightly together at the base. The midsection opens to a loose garment and exposed arms, with one hand over the heart and the other laying at the side. The head is turned away and tilts up wearing a head covering reminiscent of an Egyptian Pharaoh. The lower half of the sculpture suggests death, while the upper half suggest life and “the rebirth of womanhood, and the emergence of nationhood (Driskell, p. 108).” Fuller aimed to unify Black Africa and Black America, reconnecting and reviving a consciousness of nationhood among the Black community. For Fuller, in order to understand the idea of the Black American’s place in this country, the Black population must first recognize their collective propulsion from death, a release from a past which previously confined represented in the wrapped and mummified legs in Ethiopia Awakening.

Ethiopia Awakening, 1914, Meta Warrick Fuller, National Museum of African American History and Culture

Edmonia Lewis

Prior to Fuller’s work, few works had been created that dealt with Black identity in the America, apart from the work by Henry O. Tanner and Edmonia Lewis. An American artist of mixed African American and Native American heritage, Edmonia Lewis was born in New York in 1844, and spent most of her artistic career abroad. Although she did not create most of her work in America, her ideas on incorporating African iconography as an American-born artist remain important, as she predated Fuller by three decades. While in Rome in 1867 and working in the popular Neoclassicism movement, Lewis sculpted Forever Free in marble. Forever Free depicts a Black man standing with one foot on a weighted ball and chain and one arm raised with broken shackles surrounding the wrist. A young woman kneels at his side with her hands clasped prayerfully with gratitude. Lewis created this work two years after emancipation in the United States and had been drawn in her career to working with the idea of the Black person’s identity in America.

Edmonia Lewis

American Sculptor

In 1876, Lewis sculpted The Death of Cleopatra, a portrayal of the Egyptian ruler after the asp’s venom had taken her life. Created nearly ten years after Forever Free, The Death of Cleopatra serves in way as a predecessor for Fuller’s Ethiopia Awakening. Cleopatra in Lewis’ sculpture has taken control of her own fate, an African icon who is electively choosing to end her life, making room for a rebirth, and an opportunity to redefine a cultural identity. If this African icon represents Mother Africa, she has let go of her progenies as they embrace a new coast, a new mother land. These early works help to set the stage for Black artists of the Harlem Renaissance by bringing African symbolism and iconography back into the artistic conversation of cultural identity.

The Death of Cleopatra, 1876, Edmonia Lewis, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Aaron Douglas

Arriving in Harlem in 1924, with a bachelor’s degree in art education from the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, the American muralist and painter Aaron Douglas caught the attention of W.E.B. Dubois and Alain Locke. Through these connections, Douglas illustrated for contributions to the Opportunity, Vanity Fair, and Theater Arts Monthly (Driskell, p. 110). Douglas was one of the first to respond to Locke’s vision for Black American artists, painting on subjects relating to Black history and racial pride. Inspired by the silhouettes of people dancing at Harlem nightclubs and ballrooms, and the rhythmic sounds of jazz music reverberating throughout the city, Douglas’s paintings captured the essence of Black energy, as he painted scenes both from the Harlem and African landscapes.

Aaron Douglas

American painter, illustrator, and visual arts director

The artist’s ability to unify the ideas of African culture and history with the contemporary Black culture in a Precisionist-style was groundbreaking, earning him the consideration as “the father of Black American Art (Driskell, p. 110).” Mary Beattie Brady, director of The Harmon Foundation, was one of the small number of White supporters of Black American art, believing that there was “something innate about the way Black artists respond to auditory and visual phenomena.” Aaron Douglas’s response to the auditory and visual representations of Black culture enabled him to successfully capture the zietgiest of the Harlem Renaissance.

The Judgement Day, 1939, Aaron Douglas, National Gallery of Art

Douglas also aimed to elevate the Black role in the presence of traditional visual narratives. In God’s Trombones, a book of poems by James Weldon Johnson, Douglas painted a Black figure who stands above creation announcing the Judgment Day. According to Douglas, historically the Black figure was absent from biblical depictions, except as a servant or another supporting figure. In his series of paintings for God’s Trombones, the Black figure remains prominent in each composition. Much like the work of Meta Warrick Fuller, the presence of the Black figure as part of religious or cultural iconography reinstates the Black person as part of a cultural identity, claiming their space and the right to have a place that is their own.

Aaron Douglas and Charles Demuth: A Quick Comparison

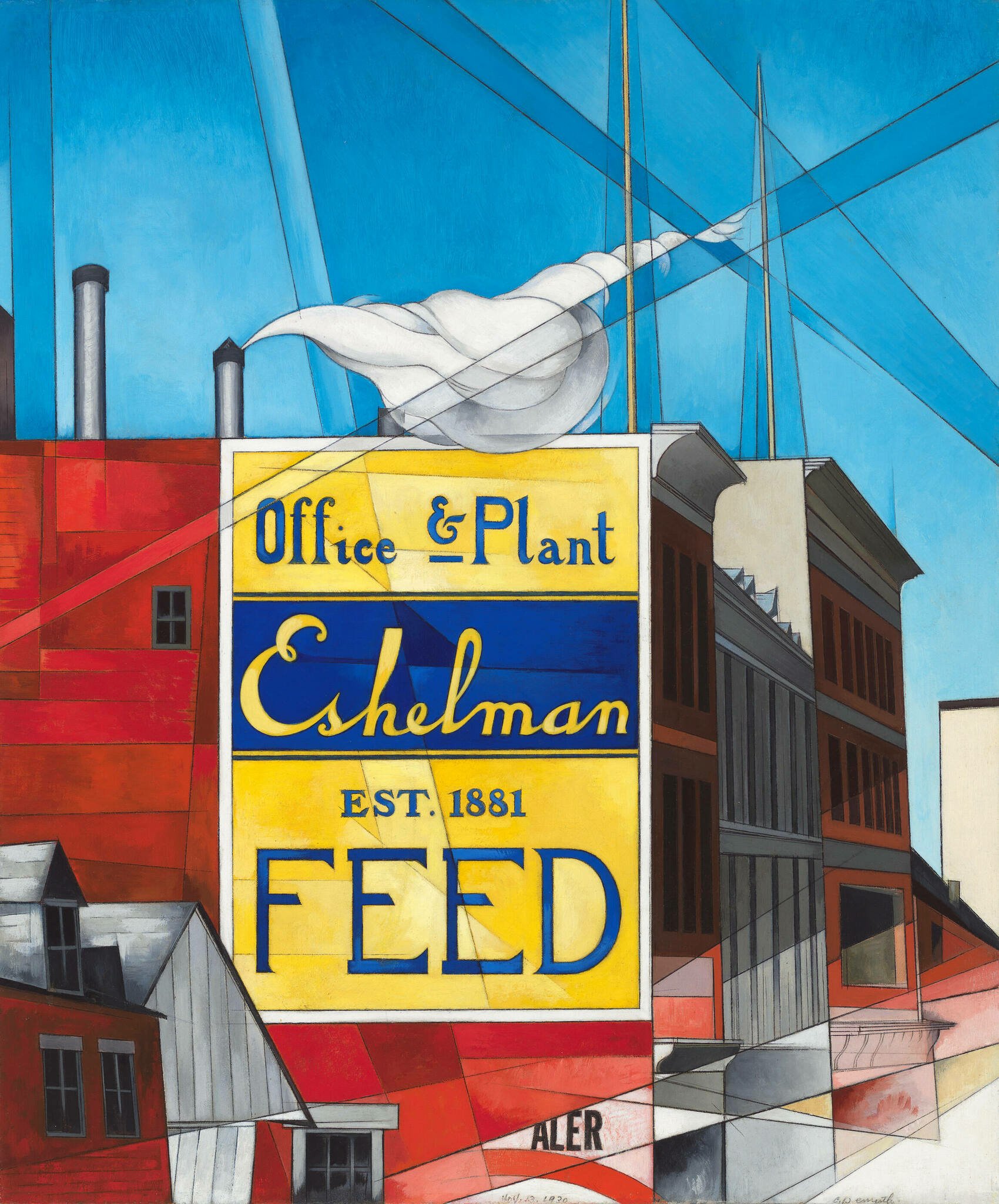

Charles Demuth was a White American painter who was known as a Precisionist painter for most of his artistic career in the northeast during the same time as Aaron Douglas. Demuth’s work was concerned with capturing the machinist age, and he achieved this with geometric forms, perpendicular lines, and fragmented planes across the canvas. Demuth was motivated by the idea of an American aesthetic, with much convincing and many trips to Europe, he started to realize the possibility of America, the newness and the ability to form modern ideas. Turning to his own landscape, Demuth began painting what he saw around him in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, that which was “provincial and uncultured by European standards (Corn, p. 220).” Demuth wondered if these humble structures would ever compare to the palatial churches and castles of Europe, yet he continued to capture his America in this way, painting the smokestacks and factories in a playful way.

Buildings, Lancaster, 1930, Charles Demuth

In comparison to Douglas’s Precisionist paintings, how could one be any more “American” than the other? Both were painting their environment, both offering a rhythmic composition suggesting movement and dynamism; however, Demuth did not often include people in his work, only the things and places which surrounded him. Douglas almost always included people in his work, and he depicted Black Americans, those who were seeking a place of their own both figuratively and literally. While speaking of Aaron Douglas, Mary Schmidt Campbell, said, “unlike Demuth or Sheeler, he does not celebrate the strength and efficiency of the industrial landscape; rather, his vision of an American machine age concentrates on the intrinsic tension between individual freedom and the grinding routine of the machine (Campbell, p. 106).” The people that are absent in Demuth’s work are not present to seek a connection to the space, the land, that surrounds them. There must be a tension between the people and the place, and place could be either geographical or cultural. People who inhabit a place are those which hold the power to endow it with value. Thomas Hardy discusses the importance of sentimentality and place in The Woodlanders: “…even though a place may have beauty, grandeur, salubrity, convenience, it still cannot be comfortably inhabited by people if it lacks memories…there being no continuity of environment in their lives, there is no continuity of information, the names, stories, and relics of one place being speedily forgotten under the incoming facts of the next (Canizaro, p. 39).” Demuth is painting only spaces and physical buildings and objects that occur in his landscape, perhaps that had value to him as a local with scenes which made up his life’s memories. However it’s the absence of a culture which defines that space that is difficult to deem as American, since the space itself could be anywhere in the world. The people present in Douglas’s paintings are characteristically Black, telling a story on the canvas of a culture’s history and pride, depicting both their former and current place. In Douglas’s work, we can see the value added to the environment by the people depicted in the paintings, activating the space and filling it with memories, names, and stories.

Dance, 1930, Aaron Douglas

A New Birth of Identity and Place

American modern art was a new movement at its time which symbolized a new birth of identity and place. Harold Rosenberg states in his essay American Action Painters that modern art is like a conversion and is essentially a religious movement. A modern artist creates their own private myths and, in their work, resurrects themselves in a moment when they were released from value (Rosenberg, p. 30-31). A newly birthed creation immediately seeks to find where it belongs and begins the long journey of discovering its identity. Black American artists, birthed from Africa and searching for their identity in America, establish their place by not simply inhabiting a space, but endowing that space with value, stories, a history, and culture.

Works Cited (in order of appearance)

Wanda Corn, The Great American Thing: Modern Art and National Identity, 1915-1935. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1999

Charles Harrison, Modernism, The Critical terms for Art History

Adolf Loos, Ornament and Crime, 2013

Yu-Fi Tuan, Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience, 1977

David Driskell, The Flowering of the Harlem Renaissance: The Art of Aaron Douglas, Meta Warrick Fuller, Palmer Hayden, and William H. Johnson, published in Harlem Renaissance: Art of Black America. The Studio Museum in Harlem and Abradale Press Harry N. Abrams, Inc. Publishers, 1987

H.W. Jansen, The International Aspects of Regionalism, College Art Journal, 1943

Donna Cassidy, On the Subject of Nativeness: Marsden Hartley and New England Regionalism. The University of Chicago Press, 1994

Vincent B. Canizaro, ed. Architectural Regionalism: Collected Writings on Place, Identity, Modernity, and Tradition. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2007

Mary Schmidt Campbell, Introduction, Harlem Renaissance: Art of Black America. The Studio Museum in Harlem and Abradale Press Harry N. Abrams, Inc. Publishers, 1987

Harold Rosenberg, The American Action Painters, from The Tradition of the New. New York: McGraw Hill, 1959

This post is from research conducted in October 2022 by Brittany Lowe.